UC scientists make biomolecular breakthrough

A team of University of Canterbury researchers has made a scientific breakthrough in biomolecular interactions, which will help discover the determinants of gene expression, in new research published today.

Discovering how gene expression is controlled is a major research question in molecular biology. Of the large amounts of variation in gene expression, the best studies can explain around 50 per cent of this variation, UC Bioinformatics Senior Lecturer Dr Paul Gardner says.

“We have discovered a previously overlooked mechanism that controls additional variation in expression. Our new approach considers the extent of how random interactions between messenger RNAs (that are translated into proteins) and non-coding RNAs can influence gene expression,” Dr Gardner says.

The UC team has proven, using some large and complex datasets, that these interactions play a major role in gene expression. The findings, which used UC High Performance Computing, have been published today by eLife scientific journal in a research paper titled: Avoidance of stochastic RNA interactions can be harnessed to control protein expression levels in bacteria and archaea, proving that stochastic mRNA and non-coding RNA hybridisation has a major impact on protein expression.

Members of UC’s Biomolecular Interaction Centre – doctoral student Sinan Uğur Umu, Associate Professor Renwick Dobson, Associate Professor Anthony Poole and Dr Gardner – were involved in the research project. Umu spent his three-year PhD predominantly working on this project after Dr Gardner proposed the original hypotheses over four years ago.

Dr Gardner says there are a number of potential biotech applications as a result of the research findings.

“Particularly in the space of designing mRNAs for genes so that protein production can be improved. We are working with colleagues at Callaghan Innovation and Powerhouse on the best way to do this.”

What is RNA?

Ribonucleic acid, or RNA is one of the three major biological macromolecules that are essential for all known forms of life (along with DNA and proteins). A central tenet of molecular biology states that the flow of genetic information in a cell is from DNA through RNA to proteins: ‘DNA makes RNA makes protein’.

About the research

Many genes carry information for making proteins. To make a protein, a working copy of the information stored in DNA is first copied into a molecule of messenger RNA. These RNA messages are then interpreted by the ribosome, the molecular machine that makes proteins. Many messages are produced from each gene, and each message can be read multiple times. Thus, it should follow that the number of messages produced dictates the number of proteins made. However, this is not the case and the number of proteins produced cannot be completely predicted from knowing the number of messenger RNAs.

Cells control how much of a given protein they produce through interactions between the messenger RNAs and other regulatory RNAs. The regulatory RNAs bind directly to a message and impede protein production. Because there are millions of RNAs in a cell, these interactions have evolved to be highly specific. Nevertheless, it seems inevitable that messenger RNAs would encounter other RNAs too, which could “short-circuit” gene regulation and lead to less protein being produced.

The UC research team asked if such short-circuit events are selected against during evolution. Computational tools were used to predict the strength of binding between the RNAs found in the dominant forms of microbial life on Earth: the bacteria and the archaea. This approach revealed that the majority of messenger RNAs bind more weakly to the most common RNA molecules found in cells than would be expected by chance. Weakened binding should prevent the RNA molecules from becoming tangled with each other and ensure that protein levels are not perturbed by unintended interactions between highly expressed messages and other RNAs.

To test this hypothesis further, the researchers generated versions of the gene for a green fluorescent protein that differed only in how well their messenger RNAs could avoid interacting with the most abundant RNAs in E. coli cells. Those messengers that were designed to avoid interacting with other RNAs yielded far more protein than those that were not.

The findings show that taking this kind of avoidance into account can improve predictions about how much protein will be produced and should therefore make it easier to control protein production in experimental systems.

Finally, the messenger RNAs of some bacteria do not show such clear avoidance. However, these bacteria have a more complex internal cell structure. This finding hints at an alternative means for avoiding short-circuiting events that could be used by more complicated cells, such of those of animals and plants, which also contain much larger numbers of RNAs.

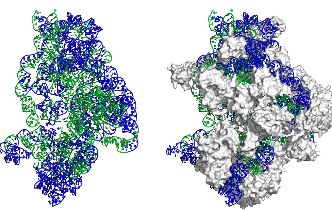

The ribosome (pictured) is the cell's protein production machine, built from some of the highest expressed genes in the cell. This image highlights that the most avoided regions of the ribosome (in blue) are found on the surface of the ribosome. These regions appear to have the greatest impact on gene expression. Those regions that are not avoided (green) are generally protected by proteins (white) or other components of the ribosome. Image credit: Associate Professor Renwick Dobson, University of Canterbury.

The link for the team’s paper is https://elifesciences.org/articles/13479

For further information please contact:

Dr Paul Gardner, Bioinformatics Senior Lecturer, Biomolecular Interaction Centre Associate Investigator, Biological Sciences, College of Science, University of Canterbury, Phone: +64 3 3642987 ext. 6742 | paul.gardner@canterbury.ac.nz

Or

Margaret Agnew, Senior External Relations Advisor, University of Canterbury

Phone: +64 3 369 3631 | Mobile: +64 275 030 168 | margaret.agnew@canterbury.ac.nz

Tweet UC @UCNZ and follow UC on Facebook