Advancing computational fluid dynamics

Swiftly solving complex computational problems may seem an obvious advantage of high performance computing but access to the new NeSI cluster is doing more for a mechanical engineering researcher than helping him to speed up his calculations.

Access to a new computational cluster is helping a researcher to solve his equations up to 500 times faster. Dr Stuart Norris is a mechanical engineering researcher working to solve computational fluid dynamics (CFD) problems at the University of Auckland. CFD solves the Navier-Stokes equations, the application of Sir Isaac Newton’s Second Law of Motion (F=m.a) to small quantities of fluid. Although they were derived over 150 years ago there are surprisingly few analytical solutions to the Navier-Stokes equations, and none for turbulent flow, so an alternative is solve them numerically using CFD.

By breaking down a three-dimensional space into a grid and applying the equations to the points on the grid, the flow at each point can be calculated. Attempting to solve these equations requires sizable computing resources, and completing a high-quality research study in this way might take months, even using multiple CPUs. Dr Norris is now using codes he programmed himself and commercially available programs to test the CFD capabilities of the new NeSI high performance computing (HPC) cluster.

The University of Auckland’s new cluster, part of the National eScience infrastructure project (NeSI), consists of 80 compute nodes, each with 2×Intel Xeon X5660 1.6 GHz 6 core processors giving 12 cores per node, and 100 GB RAM. The nodes are connected using Infiniband, and the total cluster has 960 cores and 8 TB of RAM. The machine runs the 64 bit version of the open source operating system Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5.6. Its capacity is being continuously expanded.

Solving air flow problems

The parallel computing problem-solving capabilities of systems such as NeSI make them well-suited to CFD research, says Dr Norris. “You can divide a room into sections and each of those sections runs on a different node, and the whole thing maps quite naturally to a cluster environment. All the nodes are solving the same equations but each node is looking at a different location.”

The new NeSI cluster is also helping Dr Norris to calculate the flow around the hull of an America’s Cup yacht, modelling the waves to study how the boat settles. “There’s a condition known as sink where the boat goes down in the water as it digs a ‘hole’ in the water because there’s a wave at either end, and then trim where the bow comes up. These need to be known to find the drag on the yacht.”

A third study conducted on NeSI is modelling flow around yacht sails, again using Dr Norris’s own code. Based on a parallel CFD program originally written in 1993 as part of Dr Norris’s PhD, it’s now being used in both the University of Auckland and Sydney by a variety of research groups. His PhD work in the area of natural convection and free surface flow began at a time when such studies could only be run on prohibitively expensive supercomputers and when most people were using desktop computers with, at best, Intel 486 processors.

The supercomputers of that era have today been superseded by grid computers, blade servers and other comparatively inexpensive commoditised hardware. But the advantages for science researchers of access to NeSI’s HPC facilities go beyond capital expenditure savings. They include a common services layer, simplifying access to their operating environments, as well as a scalable resource available to multiple researchers simultaneously.

Before and after

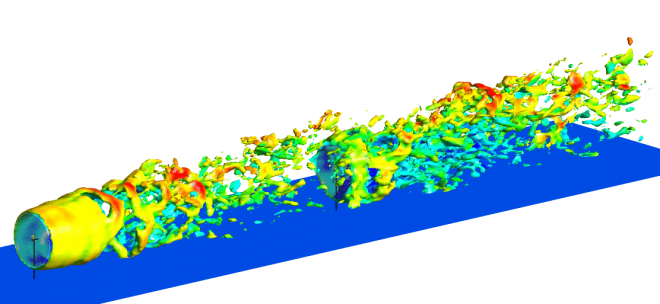

Dr Norris’s work with wind farm air flows involves studying the wake that develops as a wind turbine is affected by other turbines upwind of them. “The wind turbines upwind are fine, they’re getting clean wind, but the downwind turbines are potentially in the wake of the others and so not only get less power output because the wind’s slower due to being in the wake of other turbines, but there’s also a lot more fluctuations in the flow.” Being in this more turbulent environment may cause fatigue, causing the downwind turbines to fail unexpectedly.

Dr Norris’s group is one of only three in the world engaged in this form of wind turbine research. “We’re slightly ahead of a group in America and another in Spain, which is a sign that by having this capability we’re able to be ahead of the game because at last we have the computational resource. We couldn’t do this before and it’s opened up whole new areas to work on.”

Dr Norris was previously solving smaller mechanical engineering problems using desktop computers, but he eventually pieced together his own improvised cluster. “In its current form it’s eight desktop computers, 32 cores, with a gigabit Ethernet switch.” NeSI currently runs on 960 cores and is between 50 and 100 times faster than Dr Norris’s previous equipment – as well as around 500 times faster than the desktop computers his students use to carry out their research.

Emulating turbulence using a so-called Large Eddy Simulation also requires computational resources that can’t be replicated using DIY clusters improvised from desktop computers. The success of his tests on NeSI had made Dr Norris keen to explore other uses for the NeSI resources. “Before we had access to the cluster we were looking at flows where you modelled the turbulence – flows are turbulent, there’s unsteady motion, and you have to model it using approximations. Modelling that way isn’t very accurate and it’s especially inaccurate for yacht aerodynamics because it’s such a complex flow. Having the NeSI resource has shown us we can do Large Eddy Simulation of these flows.”

Accelerated benefits

The advantages of using parallel computing to solve science problems are readily apparent. A run that would take 24 hours on a single core runs 600 times faster on the new cluster, slashing a day’s computing work to approximately 2.5 minutes.

But the acceleration is important not only because it saves time. “You can go through and debug the process because almost inevitably on your first few runs you’ve done something wrong and there’s no point waiting 600 hours to find that out. Secondly, you have the ability to solve bigger problems. You wouldn’t fit a large problem onto a desktop computer because you’d be using too much memory. Using the cluster you can solve much larger problems, not merely because the machine’s faster but also because you have enough memory to hold the problem.”

While Dr Norris’s principal research interests are his wind turbine and yachting work, he is also looking at natural convection and river flows in conjunction with a group of researchers in Sydney. “In Australia they have problems with salination and saline pockets of water at the bottom of rivers, and they’re looking at how they’re flushed out downstream.” His code may have further commercial applications, he says. “One of them has been used in the past for bioengineering flows, where you look at flow in artificial hearts, for example, and flow within arteries and lungs.”