New Zealand’s first national river flow forecasting system for flooding resilience

The Problem:

New Zealand’s changing river levels present a constant threat of flooding, which can impact property and the local environment. River monitoring and existing local forecasting models from local councils can be sparse across the country, leading to blind spots in predicting floods.The Solution:

A high-resolution weather forecast, combined with a national-scale hydrological model developed at the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA), is using 40 years of climate data to more accurately forecast river levels across the country.The Outcome:

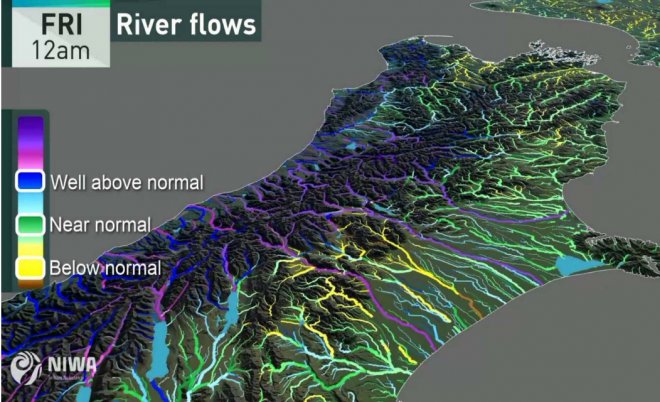

National river flow forecasts that can predict relative river flow levels up to 48 hours in advance.

New Zealand has over 425,000 kilometres of rivers and streams. Due to the country’s climate and topology, the flow of these rivers can vary greatly. Almost half of the country’s rivers and stream supply agriculture and plantations; flooding presents a constant risk to these areas, by destroying crops, damaging infrastructure and reducing soil quality. Flooding also has the potential for long-term environmental impacts for New Zealand’s native flora and fauna.

Because of this, predicting flooding across New Zealand is a priority for regional and local councils. While some councils have their own forecasting tools, there is no existing model for predicting flooding on a national level. Many poorly populated areas – including New Zealand’s west coast where flooding is more frequent – lack river flow forecasting tools.

Dr Céline Cattoën-Gilbert is a hydrological forecasting scientist for the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA). Celine leads a team that has developed a national river flow forecasting system to combat this issue. The model prototype is currently stored and run on NIWA’s Kupe cluster, but is due to transition to NeSI’s Maui supercomputer soon.

“The weather models are computationally intensive. The hydrological model which uses these weather models is not as intensive, but we run it as an ensemble. In fact, we run 50 ensembles, so that is 50 slightly different scenarios for every location in the model. This means we’re running lots of simulations with slight changes to capture the uncertainty. For these reasons, access to high-performance computing (HPC) was necessary,” Céline said.

While similar models exist elsewhere in the world, what makes the NIWA system unique is its high level of resolution. New Zealand’s mountainous terrain and unique climate mean river levels can vary wildly in a locality, so the research team needed to develop a model with enough resolution to capture these changes.

“The model has now been running for a year. We currently have 14 Terabytes stored on Kupe – that’s a lot of data. It’s calculating flow values at about 60,000 river points across New Zealand,” said Céline.

Developing the system required a cross-disciplinary approach from the team. It involved analysing 40 years of climate data collected from across the country by NIWA’s Virtual Climate Station Network. It also required hydrological modelling to analyse how climate would alter river catchment levels, as well as forecasting tools to predict future weather events and finally HPC expertise from NeSI to optimise data processing.

“Before we started, we had a consultancy with NeSI. They gave us suggestions about how to optimise code and make the program more portable. Without NeSI’s input, we would have been much more limited. We wouldn’t have been able to develop a national-scale system running in real-time,” said Céline.

“NeSI programmers Alexander Pletzer and Chris Scott helped us create automatic workflows for the software. The model must set its initial conditions from historical data, then bring in past forecasts to predict weather as it’s happening and at the same time forecast conditions up to 48 hours into the future. Without automation we couldn’t do this.”

The system can currently provide relative forecasts for river levels, which eventually could be used to inform local council stakeholders if the river is expected to be greater or less than the average expected level. Overall, Céline and her team are working towards developing a system to provide absolute values of the river levels, to give a more precise view of how the river will change. To accomplish this, the team will continue to run and store the model on Maui, as well as continue working with NeSI support staff.

Having a high-resolution river forecasting system able to cover the entire country will be vital for New Zealand, particularly in the face of our changing climate. It will help inform flood planning and resilience, potentially saving millions of dollars from damaged property, as well as helping protect the environment. Ultimately, this kind of national approach would be impossible without national supercomputing power.

Do you have an example of how NeSI platforms have supported your work? We’re always looking for projects to feature as a case study. Get in touch by emailing support@nesi.org.nz.